Portuguese Fado and Ukrainian Dumy: Echoes of Emotion in Song

What Are Ukrainian Dumy?

Ukrainian dumy are epic folk poems dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries. These deeply expressive oral compositions were traditionally performed by blind itinerant bards known as kobzari. Accompanied by stringed instruments such as the bandura, kobza, or lira, the kobzari delivered slow, recitative-style performances that blurred the line between speech and song. The melodic phrasing, often called the “duma mode,” imbued the poems with a sense of spiritual weight and solemnity.

Thematically, dumy are woven from threads of national memory and moral reflection. They recount historical events—especially tales of Cossack battles, captivity, and resistance—not to exalt military triumphs, but to dwell on the weight of human suffering. These epics do not march in praise of war; they mourn its cost, linger on the moral crossroads faced by their protagonists, and uphold the values of dignity, sacrifice, and communal truth. In this way, dumy became not only a vessel of artistic expression but a living archive of Ukraine’s collective soul.

What Is Fado?

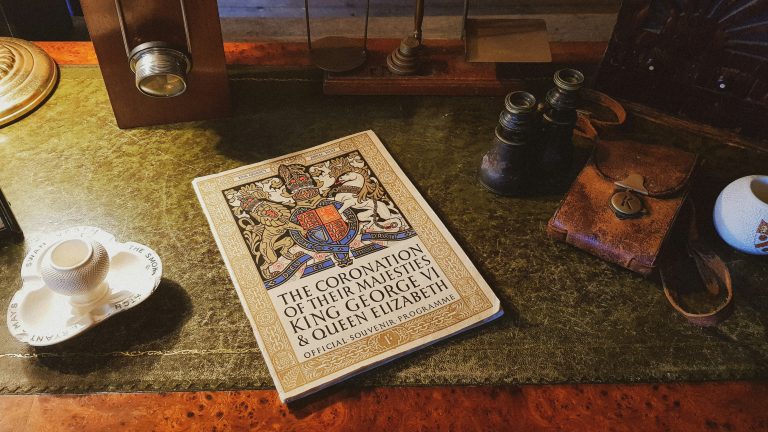

Across the continent, in the alleys and taverns of 19th-century Lisbon, another sorrowful musical form was blossoming: fado. The word fado itself means “fate,” and this tradition emerged from working-class neighborhoods such as Alfama and Mouraria, where sailors, bohemians, and street performers gave voice to the emotions of everyday life. Unlike dumy, which are epic in scope, fado is typically intimate, confessional, and personal.

Performed by a solo vocalist—known as a fadista—accompanied by classical and Portuguese guitars, fado is known for its aching, mournful beauty. At its heart is the Portuguese concept of saudade: a uniquely untranslatable mix of longing, nostalgia, and melancholy. Whether addressing lost love, missed chances, or inevitable change, fado transforms emotional pain into hauntingly beautiful song.

Shared Roots? Divergent Voices

At first glance, dumy and fado seem worlds apart in geography, history, and form. Yet when we listen closely, both traditions share a core poetic function: giving voice to sorrow, identity, and moral reflection through music.

Both dumy and fado are shaped by themes of fate and loss. The dumy mourn fallen heroes and lament historical injustices, while fado expresses personal longing, loss, and the weight of destiny. In each case, sorrow is not something to be avoided—it is something to be sung.

They are also united by their oral-recitative nature. Kobzari and fadistas alike perform live and rely heavily on the subtleties of vocal delivery and instrumental accompaniment. Each performance is a shared act of storytelling, where the audience becomes part of the emotional and cultural transmission.

Importantly, both traditions serve as vessels of communal memory. The dumy preserve historical consciousness and national values, especially during times when written records were suppressed. Fado, while often more personal in its themes, resonates with Portugal’s broader cultural identity—especially in relation to its seafaring past and colonial history.

Key Differences Between Dumy and Fado

Despite their resonant similarities, dumy and fado also differ in striking ways. Dumy are rooted in the narrative epic tradition. Their structure is loose, with uneven poetic lines that follow the flow of spoken story. They often center on moral dilemmas, heroic sacrifice, and national themes. In contrast, fado follows a more melodic and structured format, featuring strophic songs performed with precision and repetition.

The performance context also differs: dumy were often shared in open spaces, rural gatherings, or during communal commemorations. Fado found its home in the intimate taverns of Lisbon, where a small audience could be emotionally drawn into the fadista’s confessional world. These distinctions highlight how each tradition responded to its unique cultural environment.

Why They Still Resonate Today

Both dumy and fado continue to resonate because they offer something enduring: emotional authenticity. Their raw depictions of sorrow, longing, and moral tension make them timeless forms of expression. They arose from marginalized spaces—dumy from Cossack outcasts and displaced voices, fado from Lisbon’s working-class neighborhoods—and because of that, they speak with profound human truth.

These traditions also remain living, breathing cultural forces. In Ukraine, modern kobzari and folk ensembles continue to reinterpret the dumy, keeping the oral epic tradition alive. In Portugal, fado enjoys ongoing popularity, not only in traditional casas de fado, but also on global stages. It was recognized by UNESCO in 2011 as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, underscoring its cultural importance.

Listening Suggestions

For those curious to experience these traditions firsthand, there are several excellent entry points. To explore dumy, seek out performances of epic poems such as The Duma of Marusia Bohuslavka—the tale of a captured woman who outwits her captors to free 700 Cossacks—and The Escape of the Three Brothers, a stirring narrative of loyalty and fate. These works are often performed by contemporary kobzari with traditional instruments, preserving the solemn rhythm and historical depth that define the genre.

To begin your journey into fado, start with the iconic voice of Amália Rodrigues, revered as the “Queen of Fado.” Her haunting performances embody the full breadth of saudade—a sorrowful longing that defines the genre—infusing each word with aching beauty and quiet power. Rodrigues gave voice to the soul of Portugal, blending raw emotion with graceful control, and her recordings remain timeless touchstones of the tradition. From there, explore contemporary fadistas such as Mariza, who carry fado into the modern world. With rich vocals and bold interpretations, Mariza and her peers preserve the genre’s emotional core while introducing new textures that speak to today’s audiences. Whether in the candlelit corners of Lisbon or on global stages, fado continues to echo the delicate balance between fate and feeling.

FAQs

Is a duma a song or a poem?

A duma is both. It is an epic poem traditionally performed in a sung, recitative style by kobzari, blending narrative poetry with musical accompaniment.

Does fado always focus on sadness?

While fado is best known for its melancholic tone, it can also express joy, satire, and celebration. However, its signature feeling is saudade—a bittersweet longing that anchors the genre.

Can dumy and fado be compared directly?

Direct comparison is difficult because the genres differ in origin and purpose. However, their shared emotional intensity, performance style, and connection to national identity make them fascinating to study side by side.

Why was fado recognized by UNESCO?

Fado was inscribed in 2011 on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, in recognition of its cultural richness, historical roots, and continued relevance to Portuguese identity.

Are dumy still performed today?

Yes. Contemporary performers, including revivalist kobzari and folk ensembles, continue to perform dumy across Ukraine and within the Ukrainian diaspora, helping preserve and renew the tradition.

Final Thoughts

Though shaped by different histories and geographies, Portuguese fado and Ukrainian dumy share an emotional and poetic kinship. Each takes sorrow and transforms it—through song, rhythm, and voice—into a living cultural memory. In these traditions, we find the universality of human feeling and the enduring power of poetry to give voice to silence, history, and fate.